The Ultimate Guide to Stainless Steel Passivation: Nitric vs. Citric, ASTM A967 & Process

By The CNMP Expert Team

Imagine this nightmare scenario:

You design a premium medical device using 316 Stainless Steel. You machine it, polish it, and ship it to the hospital. Two weeks later, the client calls screaming—your “stainless” part is covered in rust spots.

How is this possible? It’s Stainless Steel, isn’t it?

The culprit is almost always a skipped or poorly executed step: Stainless Steel Passivation.

Many engineers treat Stainless Steel Passivation as a mere “washing” step. In reality, it is a critical chemical conversion process that restores the metal’s corrosion resistance after machining. Without it, even the best marine-grade 316 can rust like cheap iron.

In this comprehensive guide, we open the doors to our chemical processing line. We will explain the science of free iron, compare the old-school Nitric Acid vs. the modern Citric Acid, and reveal why specific grades like 303 require special handling.

The Invisible Shield: How Stainless Steel Works

To understand Stainless Steel Passivation, you must first understand why stainless steel is “stainless.”

The Materials Scientist:

“Stainless steel is an alloy of Iron and Chromium (>10.5%). When exposed to oxygen, the Chromium reacts instantly to form a microscopic layer of Chromium Oxide (Cr2O3) on the surface.

This layer is:

- Passive: It doesn’t react with the environment.

- Self-Healing: If you scratch it, more chromium oxide forms immediately to seal the wound.This is the ‘Passive Layer.’ It is the only thing standing between your part and rust.”

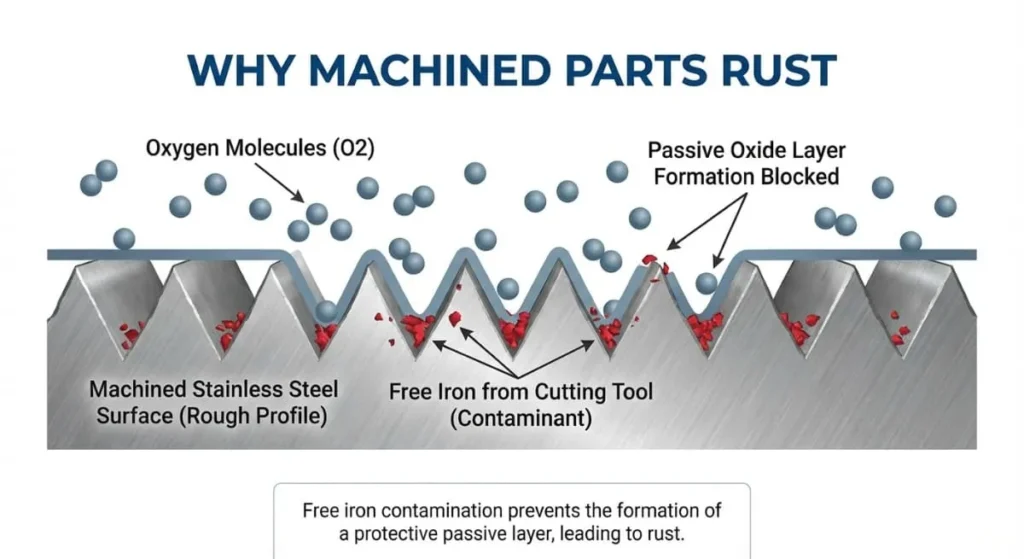

The “Free Iron” Problem

So, why do machined parts rust?

The Shop Floor Reality:

“When we machine stainless steel using CNC mills or lathes, we are violently tearing the metal.

- Tool Transfer: The carbide cutter often contains microscopic iron particles from previous cuts. These particles get smeared onto the surface of your stainless part.

- Smeared Surface: The machining process can tear the microscopic structure, burying ‘Free Iron’ on the surface.

This ‘Free Iron’ prevents the Chromium Oxide layer from forming. Instead, the iron reacts with moisture to form Iron Oxide (Rust). Stainless steel passivation is the process of removing this free iron so the chromium can do its job.”

The Process: How Stainless Steel Passivation Works

It is not just dipping parts in a bucket. A professional ASTM A967 passivation line has 5 distinct stages.

Stage 1: Degreasing (The Most Critical Step)

Before any acid touches the part, it must be surgically clean. Any trace of CNC coolant, oil, or fingerprints will block the acid, resulting in spots. We use an ultrasonic alkaline bath.

Stage 2: Water Rinse

High-purity DI (Deionized) water rinse to remove the soap.

Stage 3: Acid Immersion (The Passivation)

The part is submerged in an acid bath.

- The Goal: The acid dissolves the “Free Iron” on the surface without attacking the Stainless Steel itself.

- The Result: A surface that is chemically clean and rich in Chromium, ready to oxidize.

Stage 4: Cascade Rinse

Multiple rinses in DI water to ensure no acid remains in blind holes.

Stage 5: Drying

Hot air drying to prevent water spots.

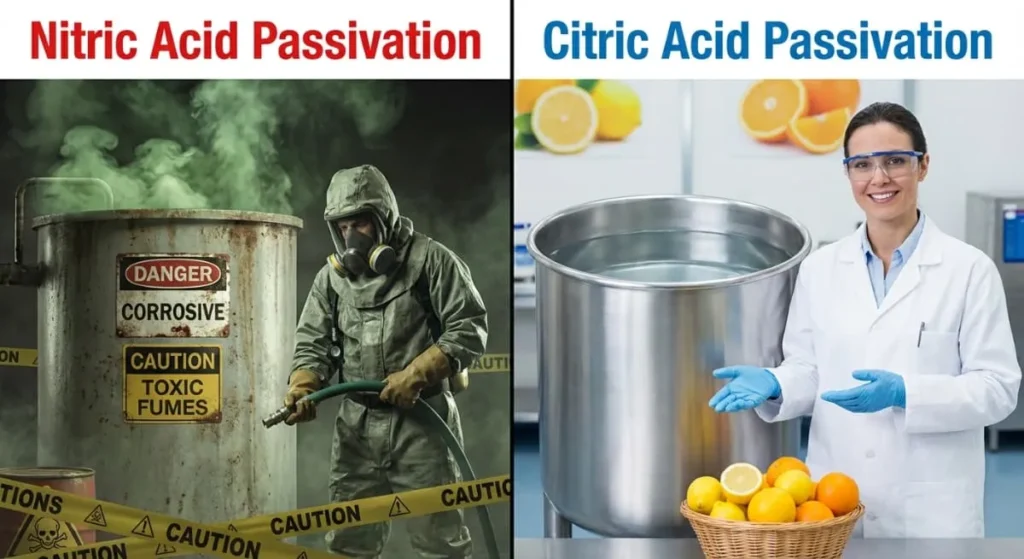

The Great Debate: Nitric Acid vs. Citric Acid

Choosing the right chemistry for your part.

For decades, Nitric Acid was the only option. Today, Citric Acid is taking over. Which one should you specify for stainless steel passivation?

1. Nitric Acid (The Old Standard)

- Standards: QQ-P-35 (Cancelled), ASTM A967 Nitric 1-5.

- The Process: A strong mineral acid that dissolves iron aggressively.

- Pros:

- Industry standard for 50+ years.

- Very effective at oxidizing the surface rapidly.

- Cons:

- Dangerous: The fumes are toxic. It requires expensive ventilation.

- Slow: Parts often need 20-30 minutes of soak time.

- Risk: If the bath ratio is wrong, it can “flash attack” the metal, turning your shiny part grey and etched.

2. Citric Acid (The Modern Choice)

- Standards: ASTM A967 Citric 1-5, AMS 2700.

- The Process: Uses organic acid (the same stuff in orange juice) to chelate (grab) the iron.

- Pros:

- Safe: No toxic fumes. Food-safe.

- Fast: Can passivate in as little as 10 minutes.

- Eco-Friendly: Easier waste disposal.

- Cons:

- Some older aerospace prints explicitly forbid it (legacy requirements).

- Less effective at killing organic bacteria (but we degrease anyway).

The Expert Verdict:

“Unless your drawing specifically demands Nitric Acid (common in legacy Aerospace), we recommend Citric Acid. It is safer for our operators, better for the environment, and just as effective at stainless steel passivation.”

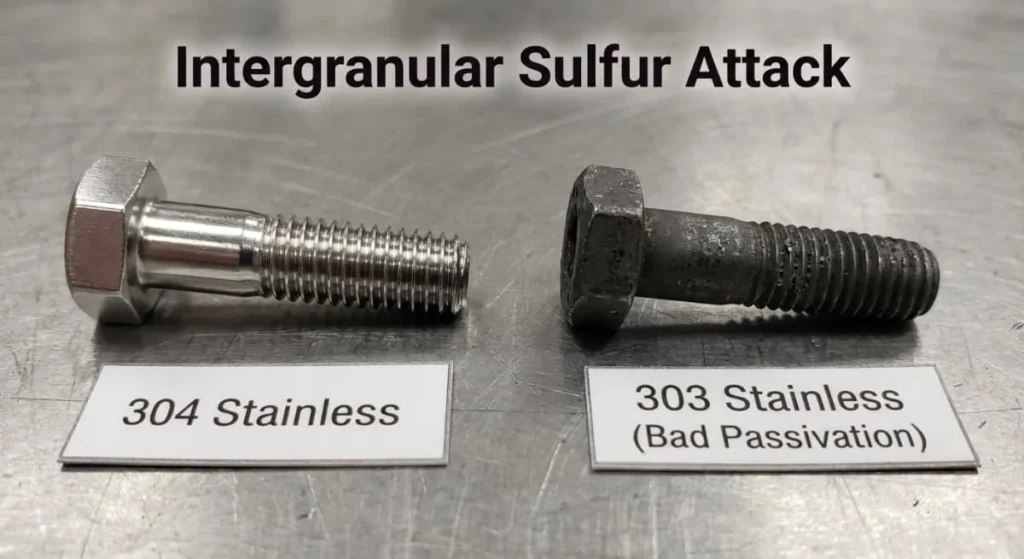

The “Problem Child”: Passivating 303 & 416

Why your parts turned black.

This is the most common failure mode in stainless steel passivation.

The Issue:

Free-machining grades like 303 Stainless and 416 Stainless contain Sulfur to help break chips.

The Reaction:

If you put 303 stainless in a standard Nitric Acid bath, the sulfur on the surface reacts violently. This is called “Intergranular Attack.”

- The Symptom: The part comes out looking black, pitted, or “frosty.” The threads are ruined.

The Fix (Alkaline-Acid-Alkaline):

For 303/416, we use a specialized process:

- Alkaline Soak: Specifically designed to remove surface sulfur first.

- Citric Passivation: Citric acid is much gentler on sulfur inclusions than Nitric.

- Sodium Dichromate (Optional): In Nitric baths, this is added to inhibit the attack (but Hexavalent Chrome is carcinogenic, so Citric is preferred).

Design Tip: If you need Passivation + Cosmetic Perfection, try to switch from 303 to 304. It passivates much cleaner.

Pickling vs. Passivation: What’s the Difference?

Don’t confuse these two distinct processes.

We often hear engineers use these terms interchangeably. They are opposites.

| Feature | Passivation | Pickling |

| Goal | Remove impurities (free iron) only. | Remove metal and scale. |

| Surface Change | No visual change (remains shiny). | Turns surface matte grey/white. |

| Material Removal | Microscopic (<0.0001″). | Measurable (0.001″ – 0.003″). |

| Chemical | Nitric or Citric Acid. | Hydrofluoric (HF) + Nitric Acid. |

| Use Case | Final step for machined parts. | Removing weld slag or heat treat scale. |

Warning: Never ask for “Pickling” on a precision machined bearing surface. It will eat away your tolerance!

How to Verify: The ASTM A967 Testing Methods

Trust, but verify.

How do you know the “Free Iron” is gone? You can’t see it. We use three standard tests to certify stainless steel passivation.

1. Water Immersion Test

- Method: The part is submerged in distilled water for 24 hours.

- Pass: No red rust visible.

- Best For: Low-cost verification.

2. Copper Sulfate Test (The “Spot Check”)

- Method: We drop a blue Copper Sulfate solution onto the part surface.

- The Science: If free iron is present, the copper will plate out onto the iron, creating a visible pink copper spot within 6 minutes.

- Pass: No pink spot.

- Best For: Quick, non-destructive testing on 304/316. (Do not use on 400 series!).

3. Salt Spray (Fog) Test

- Method: Parts are placed in a chamber with 5% salt fog for 2 hours to 96 hours.

- Best For: High-performance marine applications.

Summary Checklist for Engineers

How to specify it on your drawing.

To get the best results from CNMP, please update your print notes:

- Don’t just say: “Passivate per standard.”

- Do say: “Passivate per ASTM A967, Citric 2, verify via Copper Sulfate Test.”

Why be specific?

- Specifying Citric ensures we don’t use dangerous Nitric acid unless necessary.

- Specifying the Test Method ensures you get a quality report.

Ready to ensure your parts last forever?

Rust is not an option in precision engineering. At CNMP, our in-house Stainless Steel Passivation line ensures your Stainless Steel parts are clean, compliant, and corrosion-resistant.

Contact our Engineering Team to discuss your surface finish requirements today.